It’s February, but I have no idea what day it is.

The last weeks have been intense in so many ways. In between our other conversations, Toby has been mentioning his newest creation, Faraway Nearby.

I think most of us would agree that it’s difficult to see clearly what is right in front of us, and Toby and I have worked together a lot during the last decade.

Still, I will attempt to treat this conversation in a similar way as with the other choreographers.

I like to see these conversations with choreographers as a series of listening exercises, and I believe that the better you think you know someone, the more difficult it becomes to not make assumptions; to think that you already know what the other person is about to say. Before our conversation I’m reflecting upon what I think I know about the way Toby approaches choreography.

If I try to look at the outlines, the big brushstrokes of Tobys work, there always seems to be a process where he approaches a certain concept and looks at it from multiple angles. In his mind he builds certain images, a visual silhouette of a piece if you will, but in the center of it all is the improvisation itself.

It seems to me that it is improvisation as an embodied practice which guides Toby through everything he does; the moving core from which he is taking impulses, from the world around him, working with and against the forces of everyday life and the challenges it contains.

As I often do when I feel a bit stuck, I turn to Oblique Strategies by Brian Eno and Peter Schmidt. It’s a stack of cards with statements on them, each card offers a challenging constraint intended to help artists break creative blocks by encouraging lateral thinking. I flick through the cards, thinking “Come on, give me something good” I split the stack in half as I peek at the text:

IS THERE SOMETHING MISSING?

Well, that’s a starting point. I open the recording on my phone and start listening to the conversation that we had when Toby was in Germany teaching improvisation at the Staatstheater Saarbrücken the other week, and in my mind I visualize the pixelated image I remember of Toby on my computer screen…I’m sitting in the kitchen at home. Toby is in a big, empty apartment far away. He starts talking, in a matter-of-fact way:

-I’ve been trying to solve the task of fitting my work into the frame of Februaridans.

He explains that the theme of Faraway Nearby is very human. He points out that he usually works with more cold, pragmatic concepts. However, this time he chose to use a poetic concept as a starting point.

-It’s about feelings really. And about loss. The reality of meeting people in our lives who go away for one reason or another. To create this duet, I’ve been busy with finding out how I can work with something that I’m really interested in; how people are connected.

I ask Toby to talk a bit about the way he works with the meeting point between the poetic and the pragmatic.

–Well, I work primarily with improvisation, which basically is that meeting point. Lately I’m also part of facilitating a semi-open practice where people meet through improvising. In the past I’ve used improvisation as a choreographic tool, as a place to start. We would be recording the improvisation and then choosing and setting certain things that have emerged. This time I approach it differently. I’ve always had a little bit of a fantasy about making a dance piece in a more traditional sense, but without having any set choreography at all.

Toby speaks about how it is to be working with two very experienced dancers, Janine Koertge and Christoph von Riedemann.

– These dancers have worked with mountains of different choreographers and different styles. And they’ve embodied so many movement languages over the years. It feels like for me to just be another one of those choreographers would be a bit irrelevant somehow. I wouldn’t gain anything from it, they wouldn’t gain anything from it, and I don’t feel that the audience would gain anything from it.

So instead, I’m trying to work with them on specific ideas, searching for certain qualities that can manifest during an improvisation.

They will generate the movement live on stage, and all the movements they do will be completely spontaneous.

I ask if he can explain a bit how he guides the performers in their work.

– Their dance is generated through various directives that I offer. They are, though, full of ambiguity. I encourage the dancers to exploit that ambiguity through answering their own questions through engaging with the tasks. Very often they find more interesting strategies than I could have offered. The piece unravels through their interpretation of my directives.

I love watching people solve problems in real time. There will be a clear, time-based structure, there will be things that happen in certain spaces that will always happen there. But the actual movement vocabulary, you know, the ”steps”, I’m not going to control that. So there’s an element of trust, communication and understanding that’s developed through the process of working together. Those are elements that are very present in all of my artistic processes. I think it allows the performers to be really genuine with their presence in the performance, which in its turn offers something true to the audience.

Because they are truly present and in the now, the dancers don’t have to remember anything in an analytical way. You know, they can just BE. They can embody the ideas according to how the situation affects them and how they affect each other. It is the embodiment of that presence that is connected to the concept of loss. If two bodies meet, and one of those bodies goes away, according to the conditions that we’re working under, the body that’s left behind will not be the same as it was before the meeting.

It’s a very simple idea.

I get an image flashing through my mind of a work I recently came across, by the poet and sculptor Robert Montgomery, it’s a neon- sign in a public space which reads as follows:

“The people you love become ghosts inside of you and like this you keep them alive”

I think about how the simplicity of a single sentence, as well as a wordless emotion can hold a potential which can resonate beyond our capacity for analytical understanding.

– The concepts I’m usually busy with, Toby continues, tend to be quite complicated, both structurally, conceptually and philosophically, they tend to get very complex and difficult and it’s it’s quite refreshing and challenging to do something simple.

I ask if Toby can elaborate a bit on the embodied, sensing state that he is working with in this piece, as opposed to the more complex, complicated structures and memory tasks that he usually works with.

–A lot of the tasks that the dancers are exploring are based on sensation. It has to do with physical feeling, the feeling of touch, the feeling of being together with someone, the feeling of being alone.

I’m still working with memory. But I have introduced a few tasks that are more associative… like to search for small elements of playfulness without being specific about it for example… so what is playfulness and when can it pop up as a contrast to something else?

Could you talk a bit about the music in the piece?

– Yes, of course. The coexistence of dance and music through active collaboration with composers has been an important aspect of my choreographic work for many years. We’ve developed a nice relationship with the musician that we’re going to have on stage, Louisa Palmi Danielsson. She’s developing a palette of sounds that are going to progress and she’s going to interact with the dancers.

The performance has the strict limitation of a 20-minute timeframe, so Louisa is also going to be some sort of time master. She will give some some impulses that work as cues for the dancers so they know where they are in the timeframe.

When they’re improvising without any “steps”, the dancers can quite easily get lost in time. Louisa giving certain time cues keeps the tension between the musician and the dancers and also links them together temporally as well as spatially.

I’m asking if he has the idea of this piece staying in its current shape and form or if he sees it as a part of a bigger idea, something that’s leading to something else?

– I think at the moment I see Faraway Nearby as a self-contained idea. Its shape and form is a response to the circumstances. A part of me has come to appreciate limitations more and more because they lead me into specific territories that I otherwise wouldn’t go to. But anyway, everything always leads to something else, so actually, nothing is ever really complete.

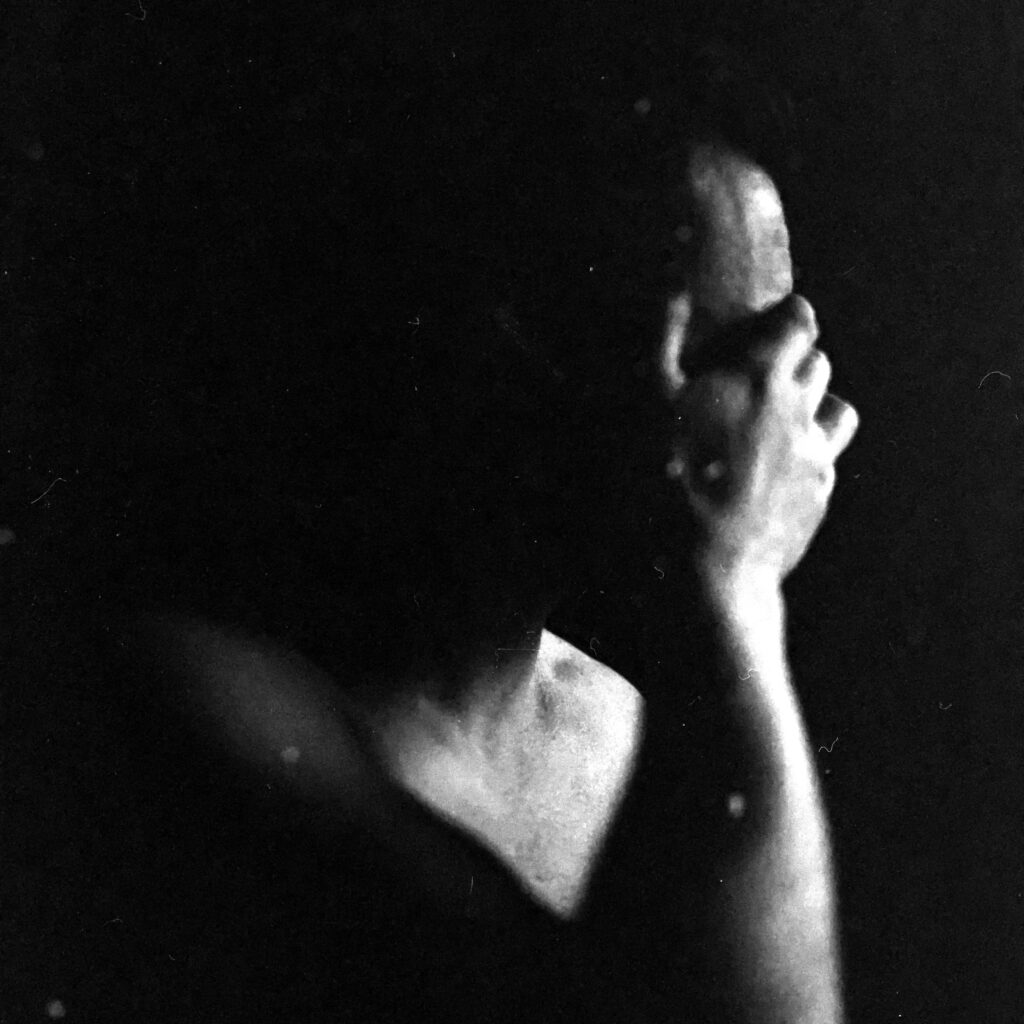

Foto: Ingeborg Zackariassen